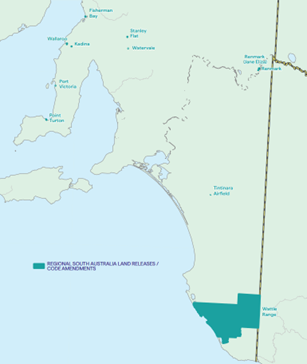

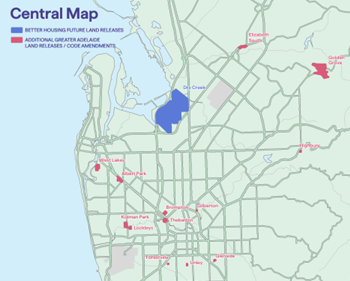

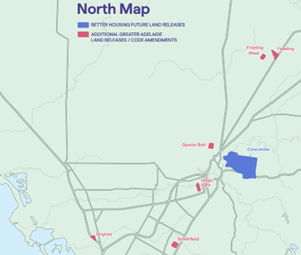

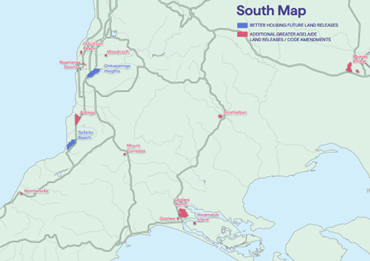

In an effort to increase supply in response to the escalating housing crisis, the South Australian government has committed to releasing and rezoning land on a massive scale (both as greenfield and in-fill) for developers, from large established outfits to small new entrants, to prepare for residents. This supplements land being brought to bear by private owners seeking to rezone their own land specifically.

The property developer is key to this plan to increase supply, and is responsible for bringing together all of the resources and labour required.

Property developers need to have arrangements with government, infrastructure owners, builders, surveyors, financiers, real estate agents, and landowners to be able to bring their vision of either a new suburb or an apartment complex to life and to the customer.

These are all essential relationships, and there are complexities to dealing with each one. This article deals with what may be the most important relationship and one whose complexities may form one of the largest current bars to new entrants – the relationship with the landowner.

Developer-Landowner relationship

A developer may assume that they receive legal and tax advice, and the recommendation of their operations team regarding the ideal structure and process for developing land, but an arrangement needs to be arrived at with the landowner themselves, and that landowner may not align with this ideal structure and process. Some time must be taken with the landowner, legal advisors, tax accounting advisors, and the operations team, to optimise process and reduce costs such as tax inside of the paradigm of what the landowner is comfortable with (or can be persuaded to agree to).

Naturally as well, the form of finance taken to fund the project will have an impact upon this – in terms of who is obtaining the finance (the landowner or the developer), the financier’s expectations regarding security for finance (which may need to be development land itself by way of first ranking mortgage, which may also necessitate that the land be otherwise free of encumbrances such as pre-existing mortgages). It will also impact on the nature of the project by way of the financier’s expectations for control of the project by the financed party subject to obligations to their financier, and in terms of the global source of the finance – if overseas, complex issues relating to Foreign Investment Review Board approval and Foreign Ownership Surcharge all need to be carefully considered.

There is a danger to being too prescriptive upon a landowner – handing them a development agreement setting out a particular model on a take it or leave it basis – as in all likelihood a development agreement cannot be created which does not flirt with unfair contract terms (which are void, unlawful, can result in huge penalties, and can generally only be saved by legitimate business purposes, which would need to be argued). To avoid being caught under the unfair contract terms regime, negotiation is useful.

Therefore, it is worth knowing the different frameworks which can be used.

Framework 1 – Take transfer of the land up-front in its entirety

This framework presents several advantages:

- absolute control over the site;

- simplification of the relationship with the landowner, such that (unless the landowner requires ongoing reporting and payments of a share of the return on the development as those returns come in) the property developer can proceed without reference to the landowner after purchase (or with minimal reference, relative to other frameworks).

In this framework, the property developer does not need to ensure that the landowner is capable of handling an ongoing complex commercial relationship, including performing their part of complex transactions periodically during the course of the development. There is therefore no risk that the landowner might, in failing to handle such a relationship and perform their part, obstruct or delay the development or cause the developer to breach other contracts.

If a developer will be retaining a relationship with the landowner and require cooperation, ensure that they have a good Will and Enduring Power of Attorney in place, or a good shareholder agreement if the landowner is a corporation, so that if they lose the ability to cooperate, a system of succession is in place over the long-term of the development.

Procedurally, the contract between the landowner and the developer is effectively in the form of a basic land sale contract, but:

- if the landowner wants to continue to use the land until it is needed by the developer, an ongoing lease can be granted to the landowner; and

- if the landowner does require ongoing reporting and payments of a share of the return on the development, a separate development agreement can be entered into addressing this arrangement. A separate development agreement will be necessary in any arrangement with a landowner requiring ongoing engagement.

This framework does present disadvantages, including the following:

- High up-front cost a significant time before income from selling lots can be expected, if the transfer is for payment up-front;

- The land may shift from being land tax exempt, to subject to land tax, upon the purchase by the developer;

- Liability and responsibility for the condition of the land as it may degrade or be damaged (including liability for environmental issues), and for managing relationships with interested parties (neighbours, easement holders, tenants if any, etc.), will all be on the developer, potentially long before the developer is ready to develop any particular section of land;

- Direct obligation to comply with the Land Management Agreements which government (local and state) may impose upon the development land. When developing land, subject to the scope of the development, the government will require these agreements be entered into and lodged on the title to development land. These agreements address integration with the neighbourhood, environmental matters, affordable housing, and infrastructure.

The sale contract should reference either that the sale is GST free as a supply of a going concern if the intention is to continue primary production or other operations on the land, or GST-free as a supply of potential residential land subdivided from farm land to which GST law section 38-475 applies (only if a property subdivision plan has already been filed by the time of sale). Pursuant to section 14-255 of Schedule 1 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth), if the sale is a supply of potential residential land to which section 38-475 does not apply (essentially if it wasn’t farmland), the developer must withhold a proportion of the sale price (7% for margin scheme supplies, 1/11th for fully taxable supplies), and pay it to the ATO upon settlement as a GST withholding amount.

Framework 2 – Take transfer of the land in stages

In this framework, the developer can take ownership at any of the following times:

- before the developer is ready to develop;

- just before the developer wants to begin shifting earth;

- when the developer begins contracting to sell allotments to residents; or

- just before settlement of sales of allotments.

The stage at which purchase should occur depends on:

- the developer’s assessment of the risk described above regarding the likelihood that the landowner may obstruct the proper transfer at the correct time required to enable the developer to develop and sell allotments. This can be mitigated in part by the landowner granting the developer a power of attorney to enable the developer to execute on the landowner’s behalf contracts which the developer would require to be executed in order to develop the land and which, as owner, the landowner would otherwise ordinarily need to execute; and

- how late the developer wants to push the liability described above regarding upfront costs, taxes, and liability for condition of the land and relations with interested parties – which depends on the developer’s cashflow and ability to fund such liabilities prior to sales.

Notwithstanding non-ownership, the developer may be required by the landowner to cover these liabilities in any event under a development agreement with the landowner. A development agreement will also be necessary to provide the developer a right to enter on the land and operate (by way of a lease or licence which would provide for a permitted use including works, erecting signage, and including the right to construct a sales office – noting that this will bring the Retail and Commercial Leases Act into application) and a development agreement will also be required to enable the developer to enter into agreements with government entities to install (depending on the scope of the development) electricity substations, gas valve station compounds, water treatment plants, landscaping for drainage, etc., before ownership is taken, and finally, for call options to take transfers of the land at the appropriate times. The nature and structure of each call option to take transfer of land is important for the purpose of reducing stamp duty.

Even if the development agreement requires the developer to take on liabilities with respect to land prior to ownership, this staged option can present a major advantage particularly if the landowner can as owner obtain the benefit of tax and duty exemptions which the developer could not itself obtain – the classic examples are primary production exemptions and primary place of residence exemptions, but also other government grants and exemptions. Some liabilities as well may only enliven upon transfer of the property from the landowner, and so there may be a benefit in delaying that transfer for that reason.

This option comes with greater complexities in certain circumstances such as for a developer of single integrated building such as a high-rise apartment complex (which will likely be subject to community or strata titling, and pursuant to relevant legislation the owner of the land upon deposit of the plan of division is considered the developer regardless) – but the developer can still delay transfer of the land in those circumstances as late as possible to obtain some of the advantages of this framework.

Framework 3 – no transfer taken at all by the developer

Especially in this scenario, it will be essential to have a development agreement which either stipulates that the landowner be more actively engaged as the party executing contracts enabling development and sale, or (more usually) which grants a power of attorney from the landowner to the developer to enable the developer to execute these contracts on the landowner’s behalf. This option provides the most straightforward model to reduce stamp duty and tax, generally speaking, but naturally necessitates the most comprehensive development agreement. This agreement needs to ensure that the developer has the ability to control all aspects of the project necessary, needs to avoid creating any trust inadvertently (which would negate many benefits), and needs to ensure that the landowner is covered for obligations arising as a result of the project for which the developer should be responsible.

Development Agreement

Particularly (though not exclusively) where the developer determines that it does not want to own the land, a development agreement is essential. In fact, under the Community Titles Act 1996 (SA), it is mandatory for staged community parcel development (and certain matters must be addressed in it under that legislation in those circumstances). Depending on the level of involvement that the landowner would like in the development project, this development agreement can take either of the following forms

- a Services Development Agreement (the landowner engaging the developer for some kind of fee arrangement as a sort of project manager);

- a Joint Venture Development Agreement in which the landowner is a more active partner (and is more often a profit sharing arrangement);

- a Sale Development Agreement, which is essentially the first framework, in which the landowner sells the land to the developer, but then retains some control over the development.

Fee structure

There are lots of models for this. The landowner can simply pay the developer a fee, or vice versa, or the developer can direct to the landowner some payment upon sale of a lot (usually either a proportion of the sale price or of the profits), or again, vice versa. Profit sharing naturally includes cost sharing as well as revenue sharing. You can even have a combination of these models – for instance, in an otherwise fee paying structure, there may be a bonus structure for achieving certain profit levels on top – or profit sharing on top of a set pre-profit payment of a proportion of the sale price. It is important in models where payment is made on sale of a lot that it is clear that such payment occurs after other essential payments are made – to the ATO and to the financier, for instance – before payment to the other party (and it may be that there is no sum to be paid after those other payments have been made).

Landowner dealings with land

Any development agreement must include provisions to ensure that the landowner does not deal with the land without the developer’s consent, or enter into any arrangements which provides an interest in the land to any third party without the developer’s consent. Unless leases are already registered over each relevant lot, encumbrances are essential at minimum with respect to every lot which is still owned by the landowner. A landowner may have a pre-existing mortgage on the land, or the land may be subject to a pre-existing lease (commonly there are leases to actual farming operators) – these will necessarily need to be removed prior to any sale (in order to sell land unencumbered), but the timing can be negotiated in the development agreement.

Developer dealings with land

The developer will usually need to be entitled not only to sell land to ultimate purchasers (either by power of attorney or by taking ownership before ultimate sale) – the development agreement will also need to ensure the landowner consents to and will provide all reasonable assistance required to enable the lodgement of interests by infrastructure owners (SA Water, SA Power Networks/Electranet, SEAGas, NBN) on the land as part of the development, and to enable the subdivisions to be undertaken and community/strata titling as applicable.

Relationship

A development needs to include disclaimers to clarify the relationship between the parties (although in practice, these disclaimers may ultimately be found to be ineffective and invalid for their purposes, particularly for a joint venture arrangement).

It is very important to set up the relationship between the parties such that a trust does not exist. The particular danger is if a constructive trust (a trust which is ‘constructed’ into existence by inference from a relationship) is determined to exist. Essentially, if principles of equity would impose an obligation upon one party to hold property in its ownership for the benefit of another, a constructive trust may be determined to exist. The result of this would be that a beneficial interest in the property would be determined to have been granted, which may be a dutiable event and an event resulting in further tax liability. For this reason, a caveat which may be considered to reflect a trust may not be a good idea (so instead of using a caveat to prevent the landowner from dealing with land, it is more advisable to effect that by terms in a registered lease or encumbrance). A trust relationship must be explicitly disclaimed in the development agreement.

Similarly, the manner in which profits are shared may result in a determination that a tax partnership exists, which has consequences including requiring partnership tax returns to be lodged, and rendering the parties jointly and severally liable – which may not be ideal. A partnership relationship should be explicitly disclaimed in the development agreement.

Split of costs and liabilities

Depending on the arrangement chosen, who is liable for what proportion of taxes will need to be considered and set out in the development agreement – usually, the developer covers this liability, and recovers as much as possible in ultimate sale as part of adjustments of rates and taxes with the ultimate purchaser.

Note: RevenueSA “advises” that adjustment can only recover land tax from the purchaser on the basis of single ownership – whereas obviously land tax is usually imposed in these circumstances on a multiple holding basis.

The developer may incur other costs throughout its ownership (insurance, operational costs, financing costs, legal costs, contract administration costs), which depending on the arrangement will usually simply be absorbed by the developer but may, by use of terms in the development agreement, be recoverable from the landowner in particular circumstances. For instance, if the landowner causes a delay which necessitates that the developer procure new Form 1s for several allotments for sale which would otherwise not have been necessary, the developer may need a provision which enables recovery in those circumstances. This also discourages delay and encourages efficient cooperation by the landowner. Alternatively, all costs may be split in a model wherein the parties share profits, in which case there may need to be a provision addressing circumstances in which costs exceed a particular budget that has been set.

A comprehensive indemnity and release clause should reference this division of liabilities.

Particulars of the development to be considered and addressed

There are other matters which need to go into a Development Agreement depending on the particular circumstances of the land and the landowner’s pre-existing commitments – it is essential to obtain full searches of the property before entering into the arrangement (essentially Form 1s including titles, dealings on titles, plans, dealings not on titles, property interest reports, EPA reports, RevenueSA certificates of tax, SA Water notices, other notices received by the landowner, Council notices, development approvals and conditions from the Council and State planning commission, asbestos reports, dial before you dig enquiries). Based on this, different obligations can be determined and divided between the parties to ensure compliance and resolution of matters. Ideally, you would obtain this information and more from the landowner as part of due diligence before proceeding with the development.

These searches are also essential to developing the sale contract to ultimate purchasers – which may need to acknowledge such matters.

Key provisions, amendments, and the ability to run away as cleanly as possible

The Development Agreement needs to include a basic design plan of the project, so that the landowner’s execution of the agreement can bind the landowner to consent to at least a basic form of the plan – with a right to provide updated, more detailed and amended plans over time.

Similarly, the first template contract for sale of lots to ultimate purchasers should be annexed, for similar reasons, with similar rights to amend.

A landowner who enters into a Development Agreement granting a developer a right to sell off their land with payment to the landowner based on sale price (either profit sharing or payment before profit), is doing so on the basis that a minimum number of lots are sold for a minimum price within a maximum timeframe. That minimum price per lot, and number of lots, and timeframe (for sale, and potentially for earlier indicative milestones such as planning approval), all need to be referenced in the agreement, with levels of flexibility. The minimum price per lot will need to be subject to any requirements by government, as particularly Land Management Agreements these days tend to stipulate a minimum number of affordable housing lots at stipulated pricing. All of this, too should be subject to a right to amendment by some process between the parties. The landowner may require that significant amendments to these matters be subject to their consent, and that gap risks where the revenue or revenue projections fall significantly below expectations, grant a right to terminate otherwise.

Over the life of a project, and different parties, the needs of the parties are going to change. Unexpected site conditions, change in legislative requirements, liabilities accruing to the land (potentially claims by neighbours or by government), failure to obtain development approval, or other force majeure events such as industrial issues, supply issues, or events which significantly affect market supply or demand, can all necessitate amendments. This amendment provision needs to account for possible causes for amendment, obligations to have meetings (which may be embedded as regular mandatory monthly meetings if amendments are expected to be needed regularly during any period), and to negotiate amendments in good faith; and damages and termination clauses for failure in this regard. There should also be an ability to simply terminate without reference to amendment if amendments will not solve an issue and changes have rendered the project impossible on any acceptable terms – although this of course needs to be carefully worded to avoid giving a landowner a right to terminate in circumstances which leave the developer significantly underwater before revenue begins coming in, including at least a dispute resolution process.

Assignment – an alternative to running away

The developer may want a first right of refusal on any sale of the land by the landowner to secure the land for themselves, or need a right to refuse or put conditions on consent to any potential buyer from the landowner who cannot bring the same benefits as the original owner – particularly regarding:

- operations to minimise tax (noting the ATO treats sale income as income taxable revenue rather than as capital gains subject to concessions based on considerations including whether the landowner has held the land for significant time prior to development);

- foreign vs non-foreign ownership (a non-foreign owner may be preferable partly to avoid issues of duty and FIRB, and partly because there are benefits to a local owner able to sign documents as and when needed in accordance with obligations).

As between the parties the option process should address circumstances in which the landowner may wish to exercise some put option in relation to the land – requiring the developer to purchase the land early. The developer, conversely, may wish to sell off all or part of their interest in the development project (either a stage, or the whole project). The lease should touch on this, but also the development agreement itself. If the developer assigns part of the project to another developer, the new developer may want to sign on to the development agreement with the landowner – naturally, the terms of that arrangement would need to be negotiated, but the development agreement often contains a template for how that would work.

Other matters

Intellectual property rights, confidentiality, insurance obligations, and GST are all relatively straightforward to insert based on the framework used and arrangement more broadly reached.

Conclusion

When approaching land development, here are some key takeaways:

- First, review the land, and the landowner;

- Make a plan, and then speak with the landowner and show them that plan;

- See if the landowner will grant you a power of attorney;

- Ensure that the landowner has their own business in order. You want to be able to ensure that cooperation continues through the years with minimal fuss.

- Expect the expected and the unexpected. There will be issues. Your development agreement needs to plan for them, and provide a clear procedure for handling them. More time up front means less hassle down the line.